Why Does the Priest “have his back to us”?

Why Does the Priest “have his back to us”?

Those of us who grew up in a totally post-Vatican II environment are accustomed to hearing about the Pre-Vatican II Mass as the one where “the priest had his back to the people.” That’s a true description, but it’s not entirely accurate. The priest only had his “back to the people” in the same sense that the person on the front row of the church “has his back” to the person in the second row of the church, and the person in the second row “has his back” to person in the third row, and so on. In the pre-Vatican II Mass, everyone is facing in the same direction. Everyone in the church is facing east.

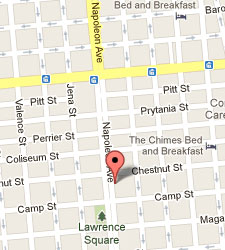

Have you ever noticed that the churches in our parish – St. Henry, Our Lady of Good Counsel and St. Stephen – are located on the downtown side of the street? For each of these churches, you enter and walk “downtown” as you walk toward the altar. This is no coincidence. Walking downtown is walking toward the east. Each of these churches is built in an “east-west” orientation. That word, “orientation,” comes from our word for “east.” That’s why we call the part of the world to the east of us the “Orient.” In the old rite of the Mass, the priest faced “ad orientem,” meaning “toward the East.”

In the Early Church the bodily posture of priest and people at the “Eucharist” was a symbol of Christian hope. Jesus Christ was identified with the dawn and the rising sun. His “dawn” (rising from the dead and then coming in glory) marks the consummation of all things and the restoration of Paradise. In the Bible, even Eden lies in “the east.” And in the Mass, not only the celebrant but the whole assembly, united in the one body of Christ, looked to the risen Lord who shall come in glory to restore all things. The Eucharistic feast is in anticipation of the messianic banquet at the end of time.

And in the pre-Vatican II Mass, celebrating “ad orientem” did not mean that the priest and the other assisting ministers faced East all the time. When they addressed the people, they faced the people. During those times, they acted as messengers from God to the people. But when the whole assembly prays to the Father, they all, laity and priests, face the risen and coming Lord Jesus.

Without getting into the differences between the “old” Mass and the “new” Mass, let’s look at some parts. Clearly, anyone can understand the reasons why the Homily should be spoken “toward the people.” It’s an explanation of the Gospels or some mystery of the Faith, and as such intended for the listeners present in the church. At many times during the Mass, the priest speaks to the people, such as “[may] the Lord be with you” or “peace be with you.”Â

But just as some words spoken by the priest are addressed to the people, many words spoken by the priest are directed to God. The first Eucharistic Prayer begins “We come to you, Father, with praise and thanksgiving, through Jesus Christ, your Son.” The second Eucharistic Prayer begins “Lord, you are holy indeed, the fountain of all holiness.” The third Eucharistic Prayer begins “Father, you are holy indeed, and creation rightly gives you praise.” And the fourth Eucharistic Prayer begins “Father, we acknowledge your greatness: all your actions through your wisdom and love.” Each of the prayers is directed toward the Father in Heaven, not toward the people. In the pre-Vatican II Mass, the sense of facing east in the Eucharist is that the priest and people are facing in a common direction oriented towards the triune God. So ad orientem is not the priest being bad mannered with his back to the people like some sort of actor on a stage, but it is the whole people of God looking with awe and joy at the resurrected Lord Jesus and in expectation and hope looking for his coming in glory.

One of the problems with celebrating Mass ad orientem was that the people often did not know what the priest was saying or doing as he prayed the Mass. That led to people praying the Rosary during Mass or dozing off. One of the calls of the Second Vatican Council was a more “active participation” in the Mass. This does not mean that everyone has a “job,” but that everyone is called to understand, appreciate and enter into the mystery of the Mass. In large churches it could mean having a good sound system (!) so that everyone could hear or preparing worship aids (like missalettes) so that everyone could read the words. But some liturgists thought it would make the whole process easier if people could see the face of the priest as he said the prayers. And so the Eucharistic Prayers began to be prayed toward the people. And unfortunate result of that “orientation” is the loss of the direction of the prayers (toward God) and the placing of the priest in a position where he sometimes feels the need to “play for the audience” who is now looking at his gestures and actions as they would look at the gestures and actions of an actor on a stage.

If you’ve never been to a Mass celebrated in the pre-Vatican II rite, you might experience something different at our 12:30pm Mass this weekend. And don’t think the priest is being rude. He’s just facing the same direction that you are already facing. He’s facing east toward the rising sun. And he’s leading you to Jesus. And the next time you’re on a plane flying to Atlanta, ask yourself this question: Would you rather have the pilot up in front flying the plane, or do you prefer him “facing the people”?